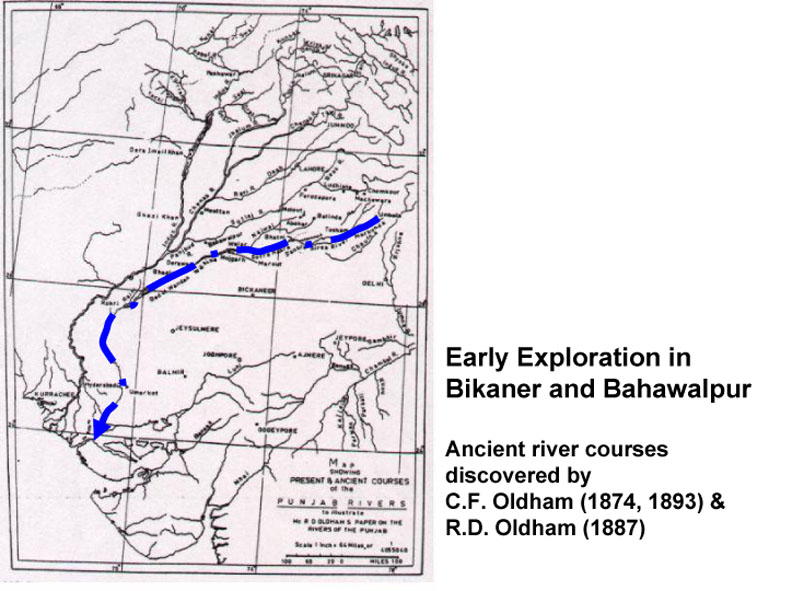

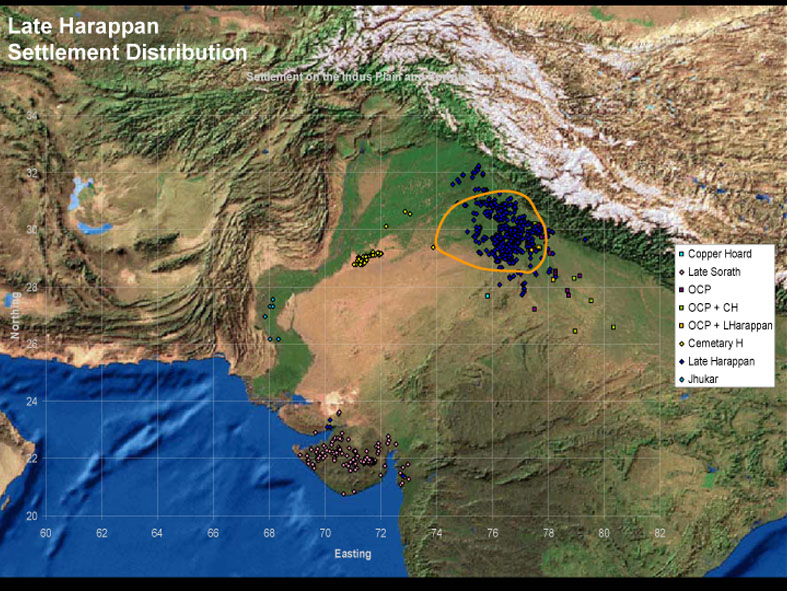

For more than 130 years, scholars have known of the existence of a number of major palaeo-channels that stretch across the modern states of Haryana and Rajasthan in India and into Cholistan in Pakistan, and it has been common to associate these with the so-called "lost" Saravati River first referred to in Vedic texts. These relic watercourses, which are today known as the Ghaggar, Hakra, Naiwal, Sarsuti, Markanda, and Chautang Rivers, were first recognized on the ground as wide channels demarcated by sand dunes, but more recently their courses have been reconstructed on the basis of satellite imagery. Much debate and speculation surrounds these palaeo-channels, primarily because they are generally believed to be the traces of a substantial glacier fed river (or rivers) that once flowed south, southwest and west across the plains of the Punjab and Haryana, thence west and southwest across Rajasthan, southwest to Cholistan, and in some reconstructions onwards to the south to flow into the Rann of Kutch. The viability of this reconstruction is seemingly confirmed by the existence of a large number of archaeological sites along these relic water courses, which has also led to the proposition that this river was instrumental in supporting some of the major sites of the predominantly riverine Harappan Civilisation. Following this line of argument, the drying up of this river is thus believed to have been one of the critical factors in the abandonment of sites in Rajasthan and areas of Cholistan, and ultimately the collapse of the Harappan urban system. The specific reasons behind the disappearance of the river are however unclear, but the prevailing opinion is that it was a result of a combination of tectonic activity and river capture, with the latter case seeing both the Yamuna and the Sutlej Rivers shifting to their courses at least once but potentially several times.

Perhaps the key factor is that despite extensive debate, as yet we have no precise dates for when these channels last carried perennial water, which has been noted previously. In fact, it is the dating of the abandonment of archaeological sites such as Kalibangan that is typically used to date the drying of the river. If we are to understand the geographical context and the human settlement systems that existed in this region, it is essential to establish the chronological and temporal relationships between archaeological settlements and their geographical and landscape contexts. For this, precise dating of the flow and cessation of perennial water in these river channels is critical and this must be combined with careful dating of the occupation and abandonment of archaeological sites in this region. Without this, virtually all of the discussion about the timing of the drying of these rivers and the relationship that this had to settled communities living along them is at best well argued speculation.

Palaeoclimate proxy studies undertaken on lakes in Rajasthan suggest that the approximate time of the Harappan Civilisation was a period of declining monsoon strength, punctuated by episodes of aridity. However, there is only limited information about past environmental conditions on the plains of NW India, particularly the summer and winter rainfall patterns during the Holocene. A potentially complicating factor is that the data from lakes in Rajasthan is not directly applicable as they are likely to have been subject to different environmental and rainfall systems.

Updated:2008-05-02. First published:2008-03-14

Copyright © 2008--2008 Cameron Petrie